Phase 2

The Unreliable Witness

(The Voice Inside your Head)

“Call me Ishmael. Some years ago--never mind how long precisely --having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world.”

It’s one of the most famous opening passages in any book. But who is Ishmael and what is his relationship with Herman Melville whose name appears to be the one you see on the book-cover? If you agree that the reader or listener must have some sort of trust in the story teller and their ability to reach some sort of satisfactory conclusion after you’ve ploughed through several hundred pages of print, shouldn’t it be kind of important to establish who exactly the story teller is and what they’re up to?

Obviously the “me” here, Ishamael, is the story teller, isn’t he?

But what happens in stories when there is no “me” to be heard:

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

And who in God’s name is in charge here?:

“riverrun, past Eve and Adam's, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.”

The first rather arch observation, as we well know, belongs to cool and dispassionate Jane Austen and the travelogue is by a clearly inebriated James Joyce.

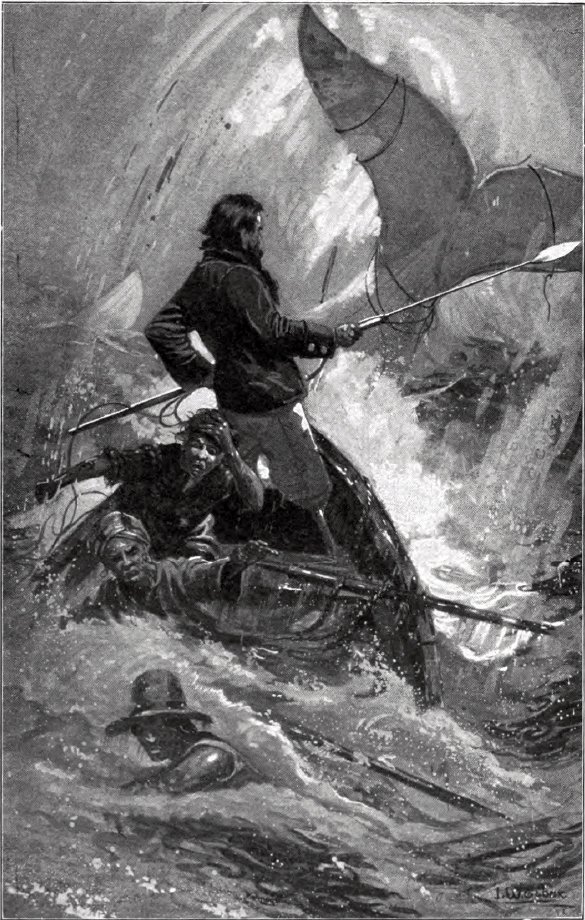

And consider that there seems to be two sorts of storytellers above: those who seemed to have actually participated in the events they describe first hand. And those who are making it all up from a distance. Ishmael definitely seems to have had an interesting life himself, and James Joyce remembers Dublin blearily from his home in Switzerland while Jane Austen never moves from her desk on the landing at Chawton and contemplates her own fate as a middle-aged spinster. Who would trust more? Tarry, whale-blood spattered Ishmael or starchy, pale Jane?

And now, I’ll let you into a secret. The narrator of “Moby Dick” is actually not this adventuresome Ishmael but the aforementioned Herman Melville who has taken on the guise of Ishmael and is using his character as a rather foggy telescope. Melville’s life is, in many respects, parallel with Ishmael’s and the fact is that the narrator is Melville giving us edited highlights and philosophy from his own life in Ishmael’s voice. So why not start his narrative by saying: Call me Herman…”?

It’s a neat trick that some writers employ; distancing themselves from their narrative for some reason by creating an intervening narrator. The narrator can be as unhinged, objectionable or downright embarrassing whilst the writer is holding up his or her hands saying, virtually “nothing to do with me. I’m just writing the story down” all the time letting the narrator do their dirty work and carry their shame. And I’m afraid to say that not even Ms Austen is guilt free in this aspect. We have got to know the reliable Jane Austen as a maiden aunt sitting quietly at her desk and hiding her papers nervously if she hears the squeak of the floor board as someone approaches. This version of Jane Austen, however, is just as much a character as Lizzie Bennett or Emma Woodhouse. And, in fact, Ms Austen’s works only achieved the sort of fame they have now when this old maid character was deliberately created after her death by the judicious burning of her letters by her family. We discover subsequently that she was in life anything but a dispassionate person and was as capable of drunken razzamatazz as the rest of us.

Of course, I know what you’re saying: that Melville chose the name Ishamael for his alter ego to nudge his readers to comparing him with the biblical character of the outcast. But, as Ishmael was also the founder of a huge dynasty we might think Melville is overstating his own claim to fame.

Probably the foremost chameleon in this line must be Daniel Defoe: journalist, pamphleteer, political satirist. And spy. A thorn in the side of the establishment who spent time in the stocks, Defoe was the greatest exponent of writing in other voices, apparently having written a detailed first hand account of the Great Plague of 1665 when he was in fact only five at the time. And who, having written in the person of Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders is rightly credited with having invented the English novel. As well as being a spy. And I draw attention to that fact to illustrate that he was a man for whom the art of dissembling came rather easily.

You presumably know that stories are fictions or, at best, only shadows of the truth but you want to treat them as the truth because that is the default you are conditioned to. Despite your twenty-first century cynicism you tend to believe what you are told. Especially if it is told boldly and bluntly enough.

You all know the tricks that writers pull with their narrators yet, you still go along with them. You only have to consider Agatha Christie’s narrator in the Murder of Roger Ackroyd. I won’t reveal who did murder Roger Ackroyd in case you haven’t read the story. But Oh what a tangled web these unscrupulous story-tellers weave and you, the gullible listeners, fall into the web every time because you leave your disbelief at the gate and follow unhesitatingly.

In the complicated dance of changing statuses between you the reader or listener and me the writer, I can go further and deeper with a less than honest appraisal of the world if I can hold my narrator at arms’ length, all the time currying favour with you. . I play upon your natural preconditioning as a member of homo sapiens to give freely of your empathy as though I am a puppy with a poorly paw.

So, when I’m telling a tale, like this one, I have to decide on a character, a voice, that is probably going to mislead you the reader: Even though you might think this is me talking to you, let’s not forget, I’m not actually here at all. If you’re reading it, it is actually you talking to yourself inside your head. Saint Ambrose was supposedly the first person who could read to himself without moving his lips. For some this was regarded as witchcraft. My written words are delivered to you like some sort of complicated speak and spell machine. And I’m disconcerted by the fact that their might be another level of distance if this being read to you in Audible.

I hide my true self from you by choosing to use words that sound pseudo-scientific or be larded with business speak jargon, I may aim to sound warm and cosy as a parent reading a bed time story or gritty and devil may care like Sam Spade. I may use an assumed voice or a slightly altered version of my own. I may try to be bold and confident in my assertions or quieter, only hinting at what I am doing. I may stand inside or outside the events which are going on. In all of them if I have a narrator I need to decide how much he or she knows about what is going on. Even when I don’t. I’m sure a psychologist would have a field day with all that.

But, in the end It is up to you to act the words out as you see fit.

As Tony Law famously said: ”Books are great but not if the acting in your head’s shit.”

In other words: it’s your fault you don’t like my story.

Anyway, let’s see if there’s anything else we can find out about story making and telling in the next episode called “Trust Me - I Make Up Stuff”

And strange to tell, among that Earthen Lot,

Some could articulate, while others not:

And suddenly one more impatient cried –

“Who is the Potter, pray, and who the Pot?” – The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam